In the season of blockbuster gallery shows and overcrowded museums, the exhibition of William Kentridge’s recent prints at David Krut Projects in Chelsea offers a much needed space for reflection. Interspersing striking large-scale works such as Lampedusa with medium-sized and smaller prints, the exhibit invites visitors to explore Kentridge’s many themes and motifs. Those familiar with the artist’s extensive body of work will pick up on the historical and conceptual narratives that run through the prints. Those encountering William Kentridge for the first time will enjoy the masterful, at times whimsical, drawings, and the lively interplay between photo engraving, drawing, collage and other forms of mark-making.

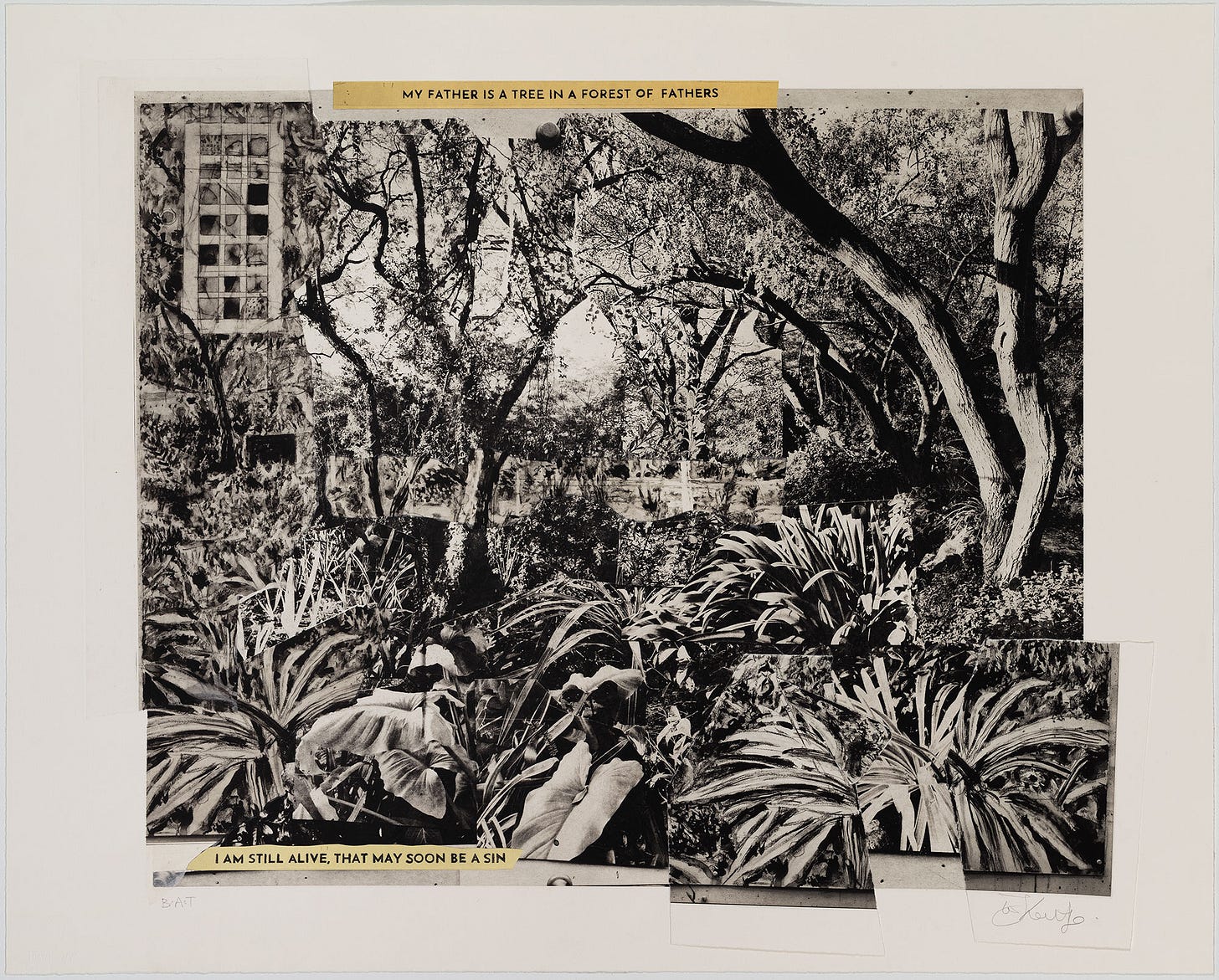

When I first saw the show on opening night at the beginning of June, my attention first gravitated to a 29”x36” photogravure of a layered landscape with the caption “My father is a tree in a forest of fathers” collaged at the top edge. As I got closer, I noticed a second caption, “I am still alive, that may soon be a sin” pasted near the bottom. The landscape in the print is at once recognizable and indeterminate: there’s lush, tropical vegetation in the foreground, trees in the middle- and background, and a cropped building—perhaps a warehouse or a factory—on the far left.

All these elements seem to originate in photographs, but the landscape as a whole appears fragmented and heavily manipulated. According to the label, Kentridge and his collaborators used Chine collé, a technique that allows collage elements to appear virtually seamless with the rest of the image. This adds to the disorienting ambiguity that pervades this and other prints.

The tree is a newer motif for Kentridge, yet it evolves out of the artist’s longtime preoccupation with the question of landscape in art. Born and raised in Johannesburg, South Africa in the era of Apartheid, Kentridge has critiqued idealized depictions of the African landscape, seeking to bring to light the often violent human history that has shaped and continues to shape it. Trees, along with cultural symbolism, bring in a more personal element into this body of work. As Kentridge has explained in interviews, trees reference themes of memory, aging and generation.

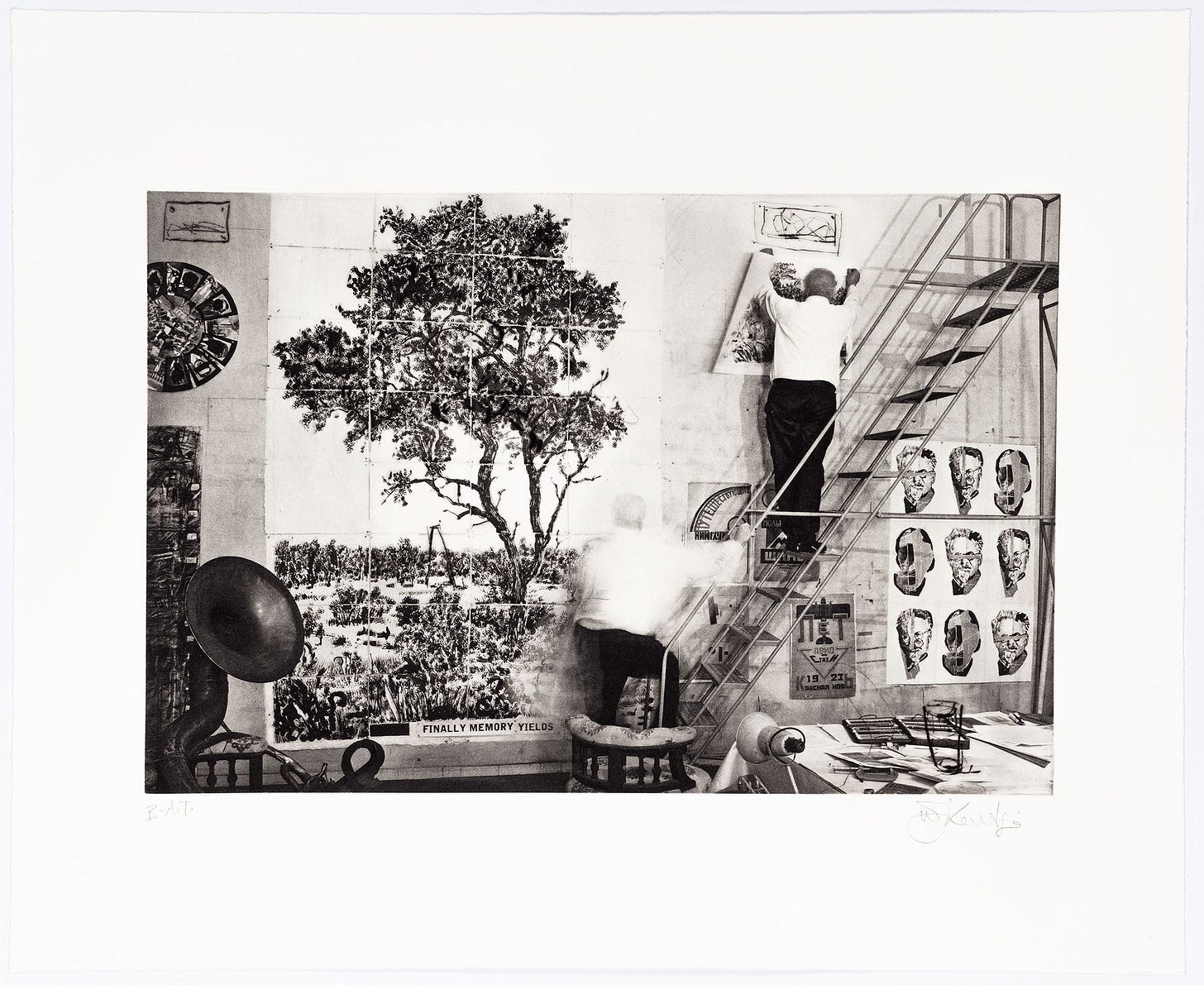

Another series of prints reflect on the creative process and the importance of openness to chance in studio practice. Perhaps Kentridge’s best known works, his animated films or “drawings for projection,” are predicated on the willingness to spontaneously modify and even erase a seemingly finished piece. Rather than using traditional animation techniques, Kentridge worked in charcoal on a single piece of paper, adding or removing marks to produce the illusion of movement. Traces of previous drawings remain visible, augmenting the expressionistic quality of the films.

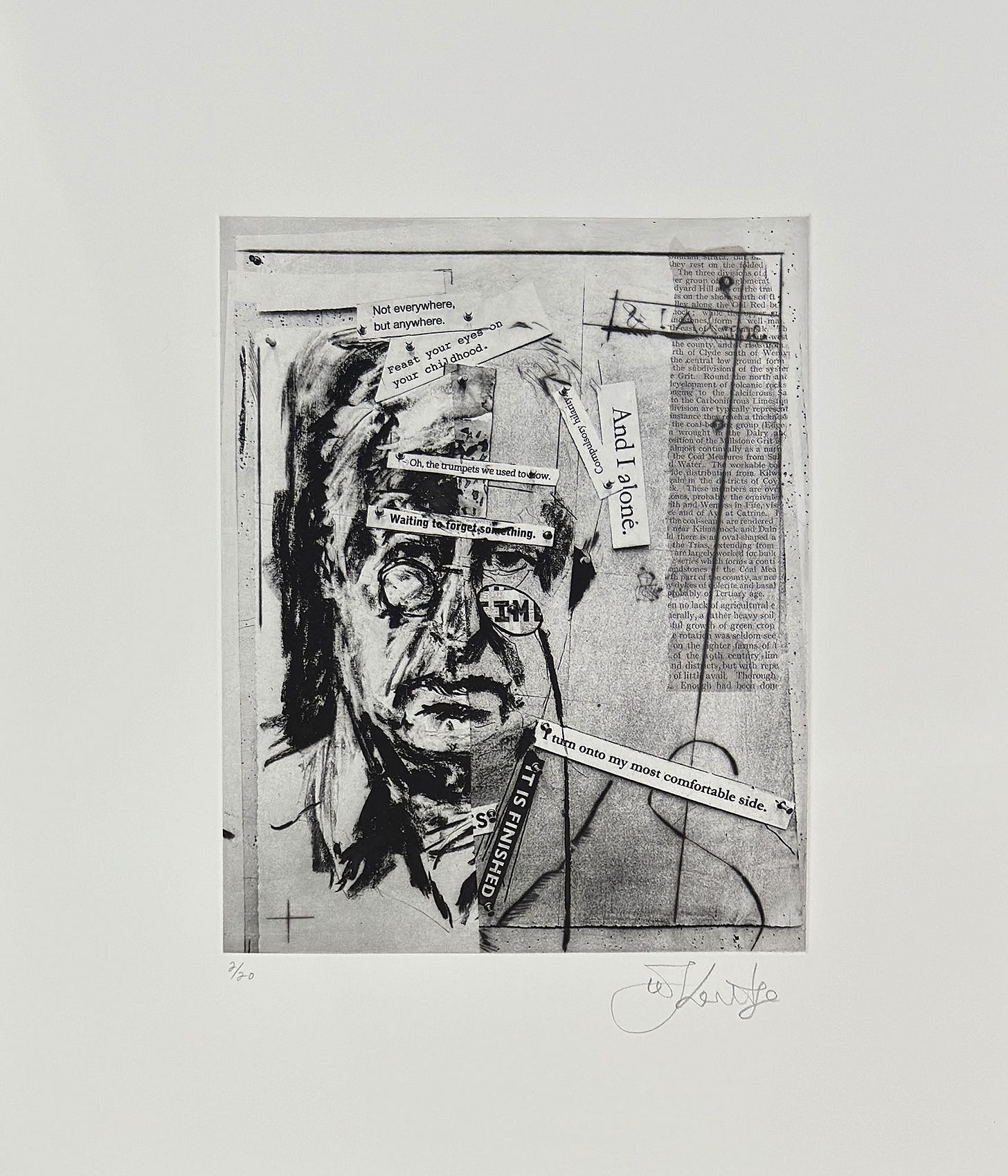

Processes of continuous addition, subtraction, and incomplete erasure are evident in almost all the prints on view at David Krut Projects. In a series of self-portraits, for instance, Kentridge’s features fall in and out of focus as collage, photogravure, texts, and expressive marks are arranged and rearranged around an underlying composition. A photogravure from the series Studio Life shows Kentridge in double exposure as he arranges prints on his studio wall. It is reminiscent of the humorous video, “Drawing Lesson” in which Kentridge interviews himself in a parody of a ponderous artists’ colloquy.

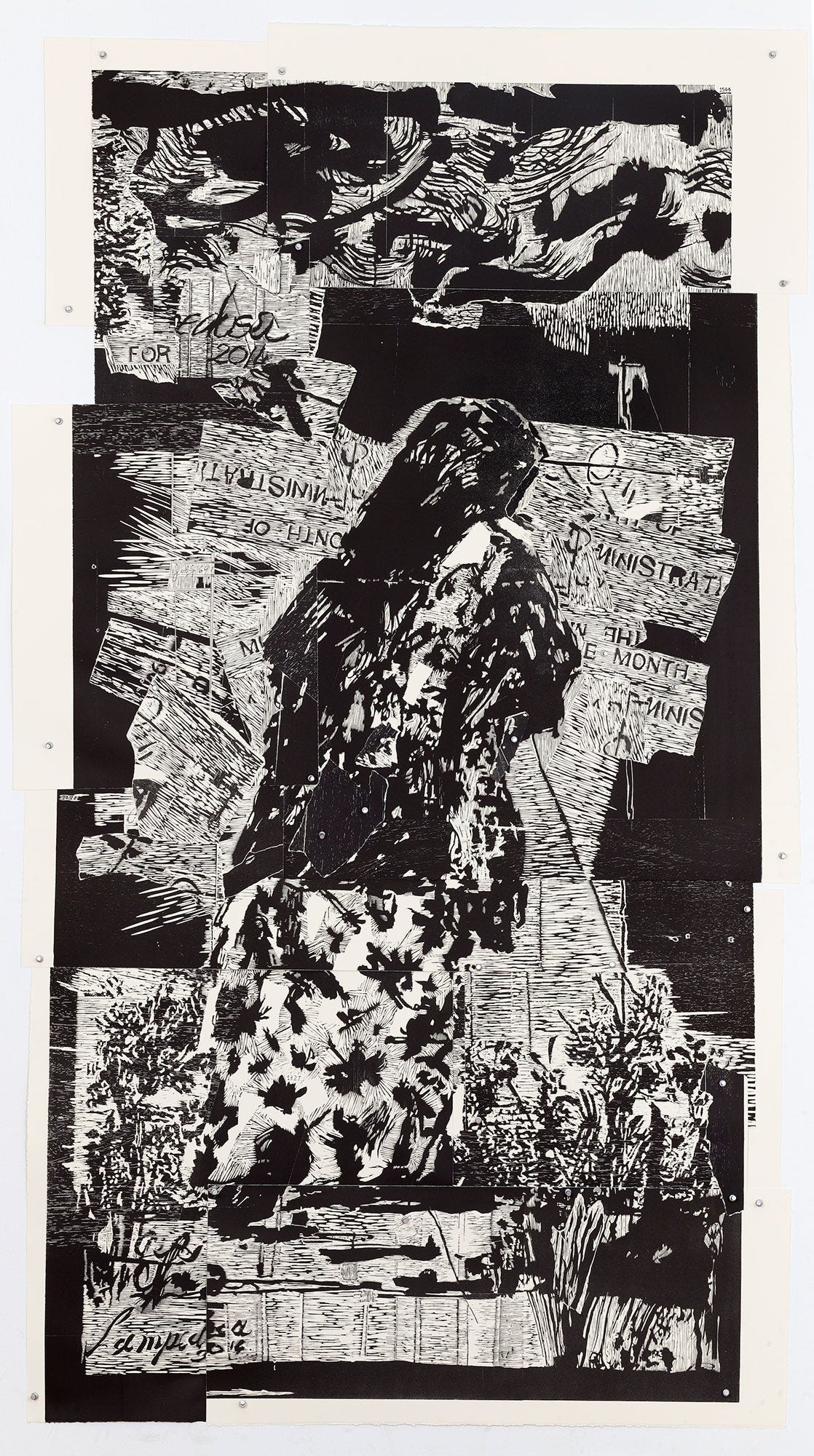

In recent years Kentridge also turned his attention to present-day migration and refugee crises. A large-scale print entitled Lampedusa shows an indeterminate figure from the back, apparently moving away. Part the “Triumphs and Laments” woodcut series, the work is a response to a shipwreck near the island of Lampedusa in which at least 368 African migrants died. Another print in the series, The Flood (not included in the current exhibit), depicts a group of large figures laboriously clambering into a tiny boat. The composition speaks to the precariousness of the journey as well as the migrant’s desperation. It is also reminiscent of earlier mass migrations—most notably the migration out of Europe during WWII. Kentridge’s own ancestors migrated from Lithuania to South Africa in the 1880’s following a series of pogroms across the Russian Empire.

Representative of Kentridge’s varied body of work, the New Gravures at David Krut Projects moves between the comical and the tragic, the whimsical and the thought-out. The show may offer the greatest rewards to those who are willing to pause and look closely at the multilayered prints, but there is much that will hold the attention of casual visitors, too.

For me, the exhibition was a much-needed reminder of the importance of the open-ended, ambiguous artistic process as a way of thinking through history. As William Kentridge often suggested, the artist in his or her studio has the opportunity to resist authoritative knowledge by remaining open to new ideas and new images as they emerge in the creative practice. As a result, the artworks, while being political, also remain open to a variety of interpretations, encouraging compassion and curiosity in the viewers.

William Kentridge: New Gravures 2022 - 2024 is on view at David Krut Projects through August 3rd.

Links and References: